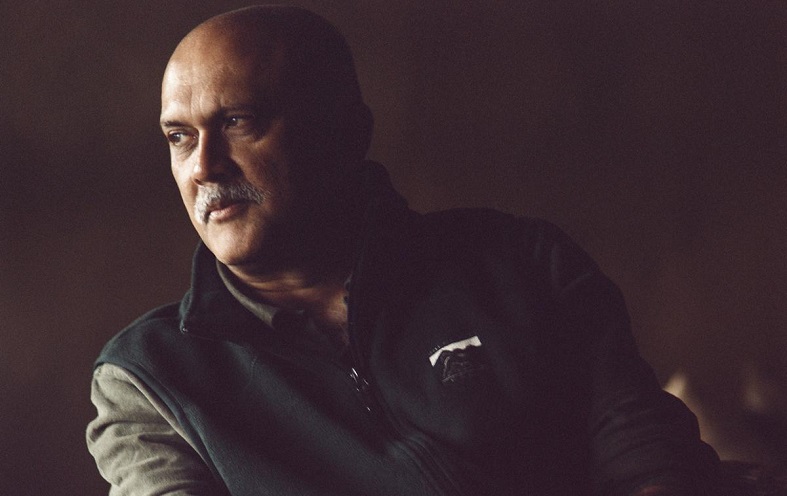

How do you shake up an unimaginative safari experience into an exciting campaign which benefits everyone, including the local communities, visitors, and even the tigers? We asked wildlife expert Julian Matthews, Founder of TOFTigers. In the interview, he explains how wildlife tourism can immensely benefit the local communities, as well as the tigers in India.

Julian’s sustainability efforts are reaping benefits in South Asia, protecting tigers from poaching and providing rural jobs, new livelihoods, and sustenance for the local population at the same time.

Julian, your work shows the immense passion you have towards wildlife. What inspired you to focus on the conservation of tigers in India specifically?

I was privileged enough to see tigers first in Bardia, Nepal in the early 1990s and it was a fabulous wilderness experience. Late in 1998 I was shocked by what I experienced in India with nature tourism in Ranthambhore. Poor guiding, poor visitor control, poor vehicles and a merry go round I did not enjoy – and did nothing for me. The fundamentals of nature tourism and its values, delivery, and implementation needed to change here, I believed.

When tigers were declared nearly extinct in 2004 in Rajasthan, with a declared 1,400 left, I knew I needed to do something – with the one industry that could be delivering conservation value outcomes – nature tourism.

What lessons or experiences from your time with Discovery Initiatives did you find the most useful when founding Travel Operators For Tigers (now TOFTigers)?

I had been privileged enough to travel the world with my own travel business, and see some of the best and worst experiences it offered for nature-based tourism.

My experience in my own country of Zimbabwe and others had shown millions of acres restored and rewilded through the advent of well-thought-out and inclusive safari and ecotourism. So I knew that if one could persuade Indian authorities to effect better policies and procedures with their tourism, we could save the tiger too – the world’s most loved animal.

You involve the local community in every stride of your wildlife tours and conservation efforts.

Absolutely – not only are locals often the most fascinating and memorable for me, and for my visitors, but they are the critical difference between success and failure in conserving landscapes and wildlife. They have to be the key stakeholders and beneficiaries of the economies generated by nature-based tourism. All too often they are not, and only good planning, goods laws, and good policy implementation can ensure this is the case.

What criteria do accommodation providers need to meet to receive a ‘Pug Eco rating’ certification from TOFT? How are you planning to make it a ‘universally recognized’ ecolabel for the travel trade?

When we started certification in 2005, there were no globally recognized criteria for ‘ecotourism’, but today there are, thanks to the Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC). So our PUG and now Footprint criteria are both based on their universal criteria. They include the whole breadth of what makes a property sustainable: from operational practices to local employment, waste to energy efficiency, water harvesting and use, to community relationships, besides others.

Today we have over 300 travel businesses involved from around the world, all committing to sustainable practices and all helping us by using our certification as a key purchasing tool. It’s a hard slog but increasingly online travel agents, who have extraordinary buying power, are asking TOFTigers for their certified properties, to highlight them on their sites so consumers can make greener choices. This is exciting when it finally happens this year, as it will drive up standards, many of which are poor and thoroughly unsustainable.

The National Tiger Conservation Authority in July 2012 proposed that tourism be restricted to 20% of the core area of tiger reserves. How can conservation and tourism work hand in hand – what kind of relationship would you consider ideal in a case such as this one?

The National Tiger Conservation Authority (Project Tiger) has had an extraordinary ‘anti-tourism’ stance for decades now, even though its core principals are based on ensuring its parks are open to visitors. This unhelpful stance has been very detrimental to the real development and implementation of quality nature-friendly tourism policy across India and remains so today.

A tourism ban from parks in 2012 was just a manifestation of the organization’s stance and resulted in the arbitrary and unscientifically justifiable 20% restrictions.

All my experience shows – and many destinations have proven this – that nature tourism needs to be a real partner in a country’s conservation efforts. If nature tourism was allowed to be a real partner in India, and not simply an encumbrance, its value to parks and local people would be greatly enhanced, and many more areas would benefit.

Today we have a heavy concentration of safari-goers in this small 20% percentage (usually much less) of any park – often too heavy – rather than having visitors spread further and thinner across all viable wilderness landscape and bordering communities. Today – and this is also due to lack of education of visitors and locals alike – benefits are too concentrated around park gate communities.

In an article for Sanctuary Asia, you highlight the sad state of affairs at Kawal Tiger Reserve in Telangana. There have been recent reports on plans to relocate tigers from Maharashtra to Kawal, and villagers being asked to move, to prevent tiger-human conflicts. Do you think this is a good strategy?

In a land with 1.3 billion people, creating space again for wildlife and biodiversity is ecologically essential, and this is not just space from humans, but from their livestock, which has historically been a big part of the problem. Less wilderness and forests result in the collapse of India’s prey species, on which so many predators depend for survival.

Many, if not all villagers within today’s strictly protected areas, want to leave, because the opportunities and facilities of the modern world cannot be delivered to them, or are heavily restricted. Their crops are destroyed by herbivores and livestock by predators.

Moving villagers are well compensated and often get new land outside a park, but it is a tough decision for them. I personally would like to see a less ‘exclusionary’ model tried here, in which parks could be more inclusive of village communities, and incentivised on biodiversity and wildlife protection more creatively. This is already happening in many community-based conservancies across the globe.

India, in its pursuit to meet its energy needs, is looking at uranium mining, which will put vast tracts of forest cover in Telangana under threat. What do you think is the future of wildlife when economy and conservation are at crossroads?

India has the expertise, skills, willingness and now monies to do what it takes to preserve wildlife and wilderness. It’s truly remarkable, given its human population, that so much still survives. Compromises will always be there. How they deal with this will be key to its future.

Which parts of your work would you consider the most difficult?

Three major obstacles – the Ministry of Environment’s and NTCA’s intransigence, the Ministry of Tourism’s poor regulatory and monitoring framework, and the lack of collective travel trade responsibility.

Which achievements are you most proud of at TOFTigers so far?

The announcement by the Environment Ministry in July 2019, that tigers have effectively doubled in the last 15 years to close to 3,000 individuals, from their dire near extinction state in 2004; it gives me the satisfaction that we have been doing something right.

Millions of visitors now have a really good chance of seeing wild tigers. Tens of thousands of once marginal farming communities now earn their living from wild tigers in much wilder landscapes than before. And this has created a massive groundswell of passionate supporters and active advocates for wildlife and conservation in the country. Many parks are now self-sufficient in funding too, thanks to park gate fees.

My only sadness: I believe much in the nature tourism sphere has happened despite Government actions, rather than because of them. It could be ten times better – and ten times more valuable.

Your 3 bits of advice for sustainable tourism entrepreneurs or business owners on how to make it work, financially?

- Think local

- Act local

- Highlight your sustainable actions/efforts – but make sure they’re real.

Thank you, Julian.

Find out about Julian’s efforts towards protecting tigers and how he includes local villagers in all his conservation efforts on his website. Connect with him on LinkedIn.

Enjoyed our interview with Julian Matthews about tiger conservation in India and his efforts towards achieving economic sustainability for the country’s rural population? Thanks for sharing!