Protecting one of the most-poached animals in India is no easy task. With the destruction of its natural habitat and questionable government regulations, safeguarding the jungle and wildlife just got tougher. But there are eco-warriors whose passion for wildlife over the years has made a dramatic difference. This is especially the case regarding the tiger population in one of India’s largest national parks: a story worth sharing.

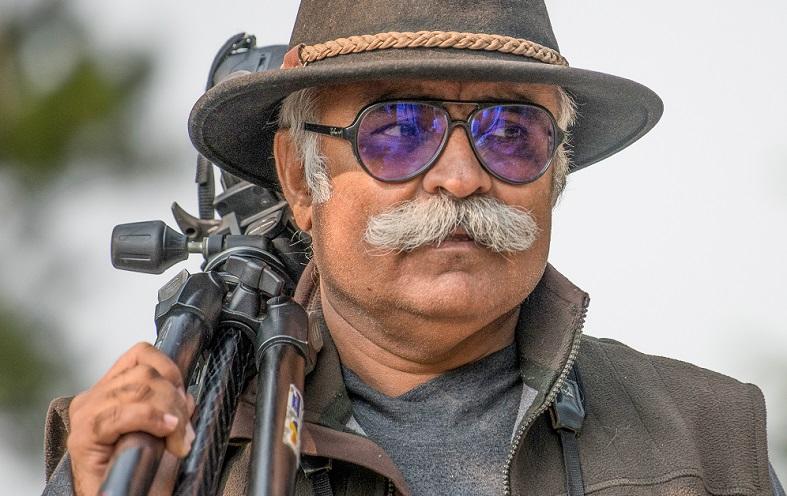

Goverdhan Rathore, the founder of Prakratik Society takes us through the arduous journey taken by his father and his organisation to restore the jungle as habitat for tigers. He explains how together they slowly won the trust of the locals and the tribes, now working hand in hand towards tiger conservation. Goverdhan also reflects on the sustainability challenges that still lie ahead for India and illustrates what needs to be done immediately to regain lost ground.

Goverdhan, your late father Fateh Singh Rathore is a renowned figure in India for tiger conservation and the revival of Ranthambore National Park. What motivated you to continue in your father’s footsteps and create the non-profit, Prakratik Society?

Growing up with my father was an adventure in the forest. In 1981, my father was brutally attacked when he tried to reason with a group of villagers illegally grazing their cattle inside Ranthambhore and he almost died. However, this changed the way park managers were looking at conservation, as a matter of enforcement rather than partnership with the stakeholders i.e., the people living around the park.

I was in Medical School in the 1980s and was very concerned about this, and was already thinking of how I could get involved to help this situation. I loved Ranthambhore and tigers. We would walk, swim, and stay in the small park guesthouses with no electricity. These were wonderful times and I could not think of living anywhere else.

Once I graduated from Medical School, I returned to Ranthambhore wanting to work with the local communities. Being a doctor, I thought that by visiting villages and providing preventive and primary health care, it would help me meet the local people and understand their needs better and what they thought about the park and its tigers.

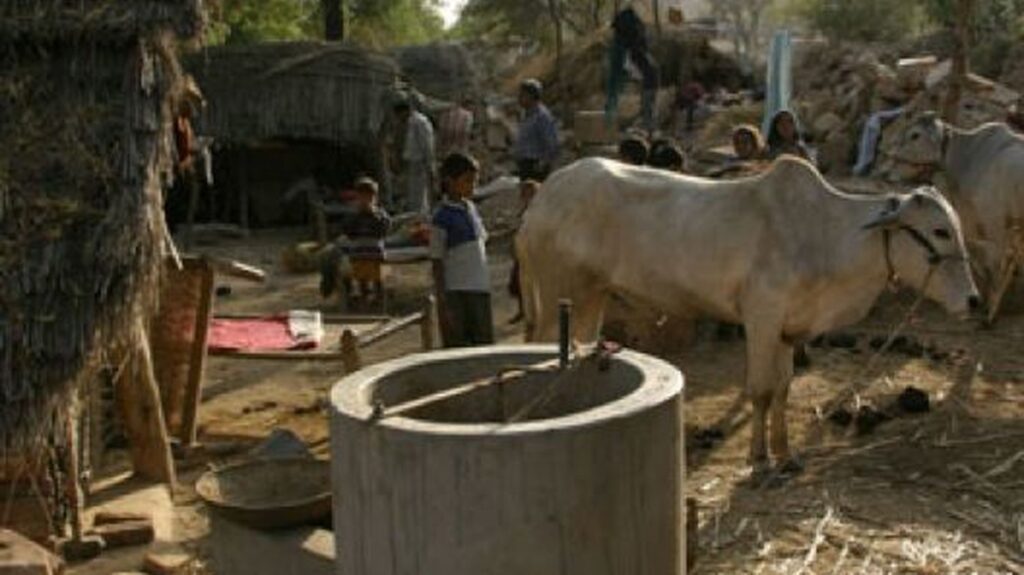

We started a mobile health care program and we would visit 33 villages every week. This provided deep insight into the minds of the people and how they thought the park gave them nothing and that it was only for the tourists that came to see the tiger. I soon realised that this battle to save the tiger would not be won unless the local people became a part of the conservation effort.

Along with a group of friends, I founded the Prakratik Society in 1994, with the objective of trying to find alternate livelihoods for the local people to help reduce their dependence on the limited natural resources of the park. So we started programs like animal husbandry and with artificial insemination, we improved the breeds of the local cattle. This way, fewer cattle could give more milk, and stall feeding could become viable, reducing the demand for free grazing in the park. Once stall feeding became the norm, cow dung became available in every home and we then started the biogas program, where we helped people build biogas digesters to create methane, which could then be used for cooking, reducing their dependence on wood from the park. Prakratik Society was a recipient of the Ashden Award for Sustainable Energy in 2004 in London.

Similarly, most houses were built using timber from the park, so we started a tree plantation scheme along the edges of the fields that would provide good quality timber after a few years. Farmers were given a cash incentive over 7 years for each surviving tree.

We worked with the local dairy cooperative run by the government to help market the increased milk yield from improved breeds of cows and buffaloes.

As we travelled through villages, we also realised that the educational standard in the region was abysmal, and without education, it would be difficult for people living at the subsistence level to understand why saving the forest and the tiger was important for their own future survival.

For the local community, it was a simple question that if their ancestors had taken natural resources from the park and grazed their cattle for thousands of years, why should there be a problem now. They could not see the impact of rapidly increasing population and therefore, demand as a problem.

In 2001, we started the Fateh Public School to help provide the highest quality education and offered scholarships to village children. Some of these children have gone on to become doctors and engineers from some of India’s premier institutes.

Prakratik Society continues to work with local communities trying to find solutions to help them understand their roles in conservation and why it is important for their future generations.

According to the latest census, India has just below three thousand tigers left – a far cry from the number of tigers that once roamed this country. What do you think are the main challenges plaguing tiger conservation efforts today?

One of the greatest challenges facing tiger conservation is the fragmenting of habitats due to the rapidly increasing population growth, putting pressure on elected governments to prioritise the economy before ecology.

Park management is the next big issue. While India has some excellent park officials who have brought back species from the brink of extinction, the absence of a pure wildlife service means park management is totally dependent on who the Park Director is. You get a good director for the park, its biodiversity thrives and if you get a bad one, it deteriorates rapidly.

There is also a lack of political leadership that further compounds the problems, as very little independent research is carried out in the parks and published. How the parks are doing is totally dependent on what the park management shares with outsiders.

The reality may be completely opposite, as was seen in 2004-05, where the park management was claiming that there were tigers in three parks when there were none. Finally, independent evaluations declared that Panna and Sariska had no tigers, and Ranthambhore had lost more than half of its tiger population.

If we need to see tigers and their habitats survive long term, one of the most important things to do would be to create a separate Parks and Wildlife Division, so that park management is in the hands of people with experience. Strategies will need to be thought of, where corridors between parks can be created. Independent research and monitoring by scientists should be encouraged and their findings published on public platforms and peer-reviewed.

A certain amount of accountability has to be placed where park authorities are held accountable for their actions.

How difficult was it to convince villagers to relocate and co-operate in initiatives under Tiger Watch?

Getting local people and the poaching community together has been a slow process, taking nearly two decades, but it is paying huge dividends. However, I would like to elaborate a little more on Tiger Watch and what it does. From the past two decades, it has been at the forefront of tiger conservation – evolving and being innovative in its approach to conservation.

While Prakratik Society was set up purely to help bridge the gap between people and conservation, there was a big gap in independent assessment of what was happening inside the park, in terms of poaching and other illegal resource extraction.

In 1991, the first incident of tiger poaching was reported by an independent undercover operation conducted by my father, even though he was no longer in-charge of Ranthambhore. He had been coming to Ranthambhore from his posting at Sariska and because he had spent so many years in Ranthambhore, he had an inkling, like a sixth sense, that something was not right. As some of the lower staff were still people that had worked with him, he started talking to them and they too said something is not right.

His undercover work uncovered a dirty nexus of rampant poaching inside Ranthambhore. He got a lucky break and passed on the information about a poacher with a fresh tiger skin travelling on a train, to the local police chief who happened to be an old friend. They nabbed this man and recovered the skin and caught the poacher. What unfolded was a nationwide outcry, and even though there was evidence that more tigers were missing for lack of independent assessment, it was covered up and the official line was that only one tiger had been killed.

However, this brought to the notice of the people of India and the world, that not all was right with Project Tiger. In 1997, my father founded Tiger Watch, an NGO with the objective of doing research and monitoring, in and around Ranthambhore to be able to provide an independent insight into the functioning of the park.

Once again in early 2002, my father had an inkling that things were not right and that many tigers were missing. Fortunately, at that time, Tiger Watch had a MOU with the government to conduct research and monitoring inside the park. A young biologist, Dharmendra Khandal, had just joined my father at Tiger Watch. He was extremely knowledgeable on this subject.

During this time, Tiger Watch had started to identify and work with some local tribes like the Mogiya who are traditional hunter-gatherer tribes and carry the stigma of being criminal tribes. Using tracking skills honed over generations and using rudimentary self-made muzzleloaders, they would easily venture into the forest at night and kill a tiger. Within hours, they would skin it and take it away, burying the body underground with salt to return later to take the bones.

Tiger Watch started to create a directory of these tribes putting together a photographic record along with the location of common residence. They are nomadic, so sometimes difficult to pin them down. Identity cards were issued and we provided free treatment to them when they came to our hospital. Slowly they began to trust Tiger Watch and we started a free hostel for their children, so they could, for the first time, go to school. As this trust formed, they started sharing information regarding how easy it was to kill a tiger inside Ranthambhore and many had already been killed.

As Tiger Watch started to analyse data from the camera traps installed by the forest department, they soon realised that 22 tigers were missing inside Ranthambhore and even submitted a confidential report to the State Government. Sadly, this was ignored and brushed aside. Not someone to sit around, my father made this report public and it created a massive national and international uproar.

Finally, even the government report acknowledged that indeed 22 tigers were missing and the most plausible reason was that they were poached. As a direct result of this, the government took the matter seriously and good officers who knew Ranthambhore well, were posted.

One of the positive outcomes of this was that the government and Tiger Watch started to partner in their work. Today, 40 children from the Mogiya tribes stay at the Tiger Watch-run hostel, their parents vowing never to kill a tiger.

Tiger Watch and the government have started a Village Wildlife Volunteer program that recruits young village folks living along the periphery of the park. They are paid a stipend and they monitor the periphery using smartphones and camera traps, passing on information in real-time through the internet regarding any poaching or any illegal activity in their area. They have now become the mainstay of information gathering in the villages, helping reduce poaching dramatically, so much so that the tiger population inside Ranthambhore has now more than doubled, with many tigers now occupying the peripheral forest areas, where there were none before.

The latest Economic Valuation of Tiger Reserves in India report mentions that those bring millions of dollars annually as economic benefits. Given the huge monetary value, how can India utilize this opportunity to develop more tiger reserves?

The potential to generate enormous revenue to further the cause of tiger conservation can only be realised if it is not always seen from a socialist lens. Wildlife tourism is a form of capitalism and the only social role it plays is to educate children and therefore, if any concession is to be given, it should be to school children.

However, the current dispensation of the park authorities is to see it as a social activity and not as a commercial activity. The result is that an incredible opportunity to generate revenue, to be able to provide incentives to villages in corridor areas to move, and therefore freeing up almost double the area for tigers, is lost.

But, just charging more money will not be enough. Efforts will need to be put to improve the experience for visitors coming to Ranthambhore. Currently, job creation through guaranteed work to guides and vehicle owners means visitors don’t have the choice of having the best. Although some changes have been made, where an additional payment lets visitors choose, but this is not how it should be; every visitor should be able to get the best service possible.

The whole scheme has taken the incentive away from guides and vehicles to better their craft, so many of the best guides have now become travel agents just booking safari for clients. This attitude has to change, a visitor to the park is contributing much-needed revenue and must be provided the best possible experience.

There should be innovative thinking i.e., higher rates in peak season and lower rates in low season, like summer, to spread the tourists out. There should be zonings like premier zones and less prime zones, and traffic and charges should be regulated accordingly.

At present, only 20% of the park is accessed by tourists. This is unwarranted because a huge area of the park is not accessed and for the most part, no one knows what is happening there. Tourists form a very important part of park patrolling and will report any illegal activity and even share pictures of tigers and other animals seen to help in establishing a better database.

How do you assess the current situation in India in terms of sustainable tourism?

In my opinion, India may have missed the opportunity to create a policy for sustainable tourism. Most of the wilderness tourism has seen a huge increase in the last two decades, however, no policy has been created to make it sustainable. The only thing that has been implemented as a policy is how far hotels can be from the park.

Once a business gets the clearance to build a hotel by meeting this criterion of distance from the park, there is no building code, there is no correlation to carrying capacity of the park and the number of beds allowed to establish. It has been a completely flawed approach. The distance policy now means many projects have come up too far from the park gate, where guests have to travel half an hour or more before they reach the park gate, adding nearly an hour to their safari which is a waste of time.

Instead, an area near the park gate should have been declared a commercial zone with building bylaws like:

- build only using local materials

- one cannot build a hotel with more than 25 or 30 rooms or construct beyond one floor

- build on 5% of the total landholding and the remaining area has to be planted with local trees of the forest so it blends in with the adjoining forest

- enough gaps need to be created between hotels for animal migration, should the zone be in a corridor

- lighting should be minimum after a certain time at night

- no DJ or loud music will be allowed and so on

More importantly, the number of rooms to be allowed should have been capped, according to the carrying capacity of the park.

An absence of this has meant that unregulated development has been allowed to take place. Rooms with more than 100-bed capacities have come up. There is no mandatory green zone per hotel. The number of rooms compared to the carrying capacity of the park is way off the mark.

What this has meant is hotels are no longer selling a wilderness experience and more and more hotels are catering to conferences, marriages, and DJ parties, all contrary to sustainable tourism. Huge air-conditioned dining halls, conference rooms, reception areas guzzle power. Tremendous pressure on the groundwater reserves is drying up wells.

There is little that can be done now, other than overrunning the park with visitors to meet bed capacity or allowing a large number of hotels to close down. The only viable escape route is to create a large enclosed tiger safari where the tourist overflow could go and see their tiger. This is the sad reality.

Your three bits of advice for sustainable tourism entrepreneurs or travel business owners on how to support wildlife conservation and at the same time ensure their own economic sustainability?

- Encourage small wilderness hotels that have a small inventory and provide a wilderness experience by encouraging nature walks and other experiences that enhance the guest’s understanding of conservation and the abundance of biodiversity.

- Find new, smaller wilderness areas to start your business. Avoid the overcrowded parks as there is no future there for tourism. Many are already saturated beyond their capacity.

- Use alternate energy as much as possible.

- Conserve water by harvesting/recycling as much as possible.

- Reduce carbon footprint by using local produce and not getting exotic foods that need to be transported in cold chain and kept in deep freezers for many days.

- Get involved with the local community to help in the conservation process.

Thank you, Goverdhan.

Connect with Goverdhan Rathore on LinkedIn. Find out more about Prakratik Society and what they do on Facebook.

Enjoyed our interview with Goverdhan Rathore on how empowering locals helps in achieving wildlife conservation, and how India badly needs a sustainability strategy for its tourism development? Thanks for sharing!