From biologist to business consultant, Ariane Janer has spent decades developing an in-depth understanding of sustainable tourism and the complexities of the industry that surrounds it. In this interview, she shares with us her journey from conservationist to sustainable tourism leader and innovator, thanks to her work as co-founder of EcoBrasil (The Brazilian Ecotourism Association), as a founding member of the Global Ecotourism Network (GEN), and as the owner of the successful sustainable business consultation firm, Bromelia.

Ariane also explains the challenges of positioning a country as large and diverse as Brazil as an eco-destination, and how GEN will draw on its vast accumulation of experience to help guide the international sustainable tourism industry in the right direction.

Learn about:

- The key elements in improving the quality and sustainability of tourism businesses;

- Why location and cost affect sustainable tourism development in a country as large and diverse as Brazil;

- What to keep in mind when partnering with government, tourism trade and conservation NGOs;

- Key challenges of maintaining the appeal of a good ecotourism product;

- How the Global Ecotourism Network (GEN) helps the ecotourism industry to focus and progress.

Ariane, as a biologist, you were probably aware of the concept of conservation and sustainability early on. When, however, did you first learn about sustainability in relationship to tourism?

First I learned about “the dots”, and then I managed to connect them.

Ever since I was a child, I was interested in animals and nature. My aunt gave me a gift membership to WWF Holland. My parents traveled to far-off places when we were very young and always came back with lots of stories. We avidly read National Geographic, learning about places all around the world.

When we started to travel as a family, there was always an itinerary with a narrative and a learning experience, and it combined nature, culture and relaxing at the beach. My parents planned everything in detail. In those days, you did this by letter, telegram, a fixed phone and a guidebook. Sustainability was not an issue then, there seemed to be a lot of space in the world.

During high school, I became increasingly aware of environmental issues. Things like Limits to Growth, the oil crisis of 1973 and the car-less Sundays, acid rain, a heavily polluted river Rhine and a major toxic waste scandal come to mind.

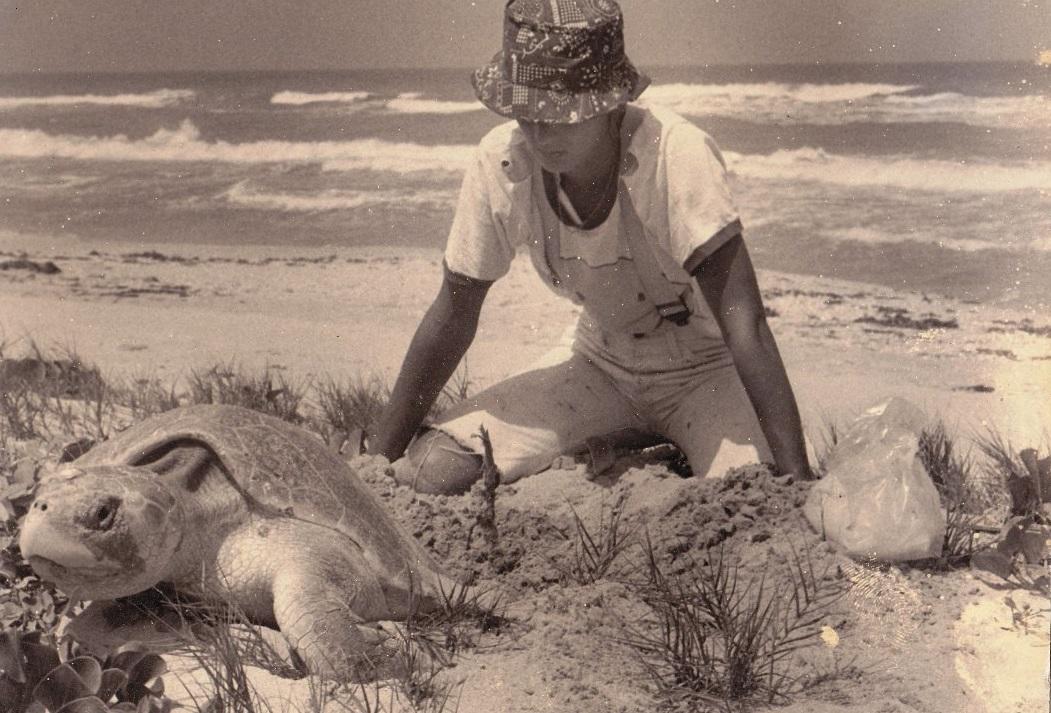

My “sustainability in tourism moment” probably came in Mexico. I did my final thesis for my MSc in biology on sea turtles and spent a year in Mexico. We patrolled and collected data on many beautiful beaches. When I visited Cancun in 1981, it was still under construction.

It was horrifying to see the great contrast of a mega resort with the (then) relatively untouched neighboring places on the Yucatan peninsula. Big resorts also do not combine well with sea turtle nesting beaches. In Mexico, I also became much more aware of the importance of the local community for both conservation and in tourism.

What made you decide to make the professional transition into the sustainable tourism industry?

First, I decided I needed to learn more about business in order to help nature. For my MBA thesis, I was lucky enough to be able to study a long-term WHO project in West Africa on the management of the control of River Blindness (Onchorcerciasis). This terrible disease is transmitted by blackflies, who breed in flowing water and thus affects those living and farming close to rivers. This opened my eyes to another reality: the importance of very basic health and security conditions for communities.

I started working at Shell, hoping to learn about management and also travel to other countries. At the time, I thought that there could also be a future there in alternative energy. After about three years working in Holland, they sent me to Brazil.

After a year, I met my husband there. Next to running his own business, he was supporting some pioneer conservation initiatives in Brazil. At the same time, I realized that I would not have a career in alternative energy, as it was not really a priority for Shell. If I wanted to stay in Brazil, I needed to do something else.

Friends of mine had started one of the first ecotourism operators in Brazil. One of the founding partners and an ecotourism pioneer was Silvana Campello, a biologist who had organized the first official ecotourism guide course in Brazil for Embratur in 1987. She had just been offered a dream job at the World Bank and the partners were looking for a replacement. So I switched.

You have been the owner of Bromelia Consult for a quarter of a century. The business started out as an ecotourism operator and has expanded into a well-respected consultancy for sustainable development in the tourism industry. Can you tell us more about the first incarnation of Bromelia and how it has evolved over the years?

It was a lot of fun running a small ecotourism operator in Brazil, researching, setting up and operating tours, being a guide, training guides and marketing to international tour operators. Just when we started out, we were asked to set up a day tour to visit the Golden Lion Tamarin Conservation Program near Rio. This beautiful little monkey was in danger of going extinct in the wild. During Rio 92, this was quite a hit with the delegates.

But despite these small successes, business-wise, the timing was a little off. Brazil was in an economic crisis, international tourism was down by 50% and the country was not considered a reliable destination for ecotourism by international tour operators. On top of that, airline travel to Brazil was more expensive than to competing destinations. So, demand was low and you had to compete with conventional operators, who had much more marketing clout. Unfortunately, my partners did not have enough capital to hold out for better times and, though we got close, we did not manage to raise venture capital. My two children were born in those years. I decided I could not do it alone; tourists and toddlers demand a lot of attention.

Bromelia went into hibernation, and I made money being a freelance consumer market researcher for Euromonitor and later added being a financial analyst at a boutique investment bank called Baxter Straub. These experiences were key for reinventing Bromelia as a consultancy for sustainable businesses (not only tourism related). The focus was on tailor-made business plans, marketing research, strategy and training. I also worked on larger projects as part of a team. A good example of the latter is the Brazilian Program for Certification in Sustainable Tourism (PCTS in Portuguese), which was coordinated by the Hospitality Institute and financed by the IADB, Ministry of Tourism, APEX (Brazilian Export Agency) and SEBRAE (Small Business Support System).

The main objective was improving on the quality and sustainability of the medium and small tourism businesses in Brazil, through standardization, training and technical assistance, certification and marketing. I was part of a core team of quality, standardization and sustainable tourism experts. The program was targeted at hotels at up to 50 rooms and reached out to stakeholders in key destinations in Brazil.

You co-founded EcoBrasil (the Brazilian Ecotourism Association) in 1993 and stayed on as Technical Coordinator until 2014. What was the creation process of the organization, and what were some major projects or initiatives that took place during your time there?

Many of the Brazilian ecotourism pioneers at the time met at an Ecotourism Congress in Ilheus in 1993. The organizers used a pretty girl on a donkey at the beach as the cover of their promotional pamphlet. They didn’t understand what ecotourism was, but they knew it was trendy. We put our heads together and concluded we needed to organize ourselves better and formally founded EcoBrasil at the Adventure Travel Congress (organized by the Adventure Travel Society, which later became ATTA) in Manaus. Our inspiration was The Ecotourism Society (TES not TIES at the time) and Megan Epler Wood and many other international pioneers were there at the conference. Most of the original founders of EcoBrasil are still leaders in ecotourism and sustainable tourism in Brazil and internationally.

In the 90s, the emphasis was on investing in people by spreading knowledge and providing training about ecotourism.We partnered with the government, experts in different areas and major NGOs on projects like Ecotourism Guidelines for Brazil (1994), WWF Brazil’s Community Based Ecotourism Program (1996 – 1999), Pilot Program for Ecotourism in Indigenous Areas (1997), Funbio’s Best Practices in Ecotourism (2000 – 2003), Braztoa’s International Benchmarking in Ecotourism (2004 – 2005).

Gradually, the focus of interest of the government shifted more towards sustainability in tourism, adventure tourism, social inclusion and community-based tourism and using standardization and certification as tools for promoting quality, safety and sustainability.

New organizations have been created. ABETA (Brazilian Trade Association for Adventure and Ecotourism) reflected a growing necessity to help businesses become more professional. ABETA also extended the work of the PCTS into safety and adventure tourism activities standardization and certification and has brought this to the international stage.

The NGO Semeia is now promoting Public-Private Partnerships to support tourism in protected areas and has managed to push the public sector.

What challenges did EcoBrasil face in regards to ecotourism development in Brazil and positioning the country as an eco-destination?

It is important to realize that EcoBrasil was just one of many organizations working with tourism, conservation and communities. On the national level IEB (the Brazilian Institute for Ecotourism), was also doing good work. For instance, they did an extensive inventory of potential ecotourism destinations in Brazil.

Brazil is a huge country with a large domestic market. Though it was often seen as one destination in the eyes of the international market, it always was a country of many destinations. To get the word out to the field, you faced logistic problems or, simply put, needed to spend money on travel.

Partnerships with the public sector, tourism trade, conservation NGOs and development agencies were essential. WWF Brazil, Conservation International, The Nature Conservancy, SOS Mata Atlantica were some of the NGOs supporting ecotourism.

The word “ecotourism” had immediate marketing appeal. The conventional tourism trade and governments from national to destination level, saw it more as some kind of fairy dust you could sprinkle on nature tourism in general. The much vaunted growth numbers of 15-20% per year, seemed especially appetizing to the short term thinkers. So, when partnering with government, tourism trade and conservation NGOs, you had to be careful to manage expectations, without losing interest.

Serious private investors, were not that gung-ho on the tourism sector in general and, even if they were, they were more interested in large projects than risky small-scale ecotourism ventures. Many investments funds, even those with an environmental focus, were looking for high IRRs (over 20%). In Brazil, interests rates have always been high and just the transaction cost of getting a loan is a barrier for small business. So, many ecotourism ventures were self-financed and/or received seed money or support from NGOs or government programs, like the Proecotur (IADB funded Ecotourism in the Amazon Program). Not all of these investments were wise, but many of Brazil’s top ecotourism products established themselves in the 90s.

Efforts were also made to implement a concession system in National Parks, but despite setting the example of Foz de Iguaçu, the combination of bureacracy and barriers to entry for small businesses meant that this is still waiting to take off.

It is challenging to maintain the appeal of a good ecotourism product in a destination that is not sustainably managed. And destinations are always in danger when short term economic interests like mining, oil and, sadly, big tourism arrive with big promises and then leave the local community with empty hands.

Or in the case of the Samarco mining dam disaster with a terrible legacy.

You are a founding member of the Global Ecotourism Network (GEN). What prompted the organization’s creation? What makes it different than all the other sustainable tourism organizations out there?

EcoBrasil had been working with TIES [The International Ecotourism Society] since 1993. In 2010, I was asked to be part of what proved to be the last Advisory Board of TIES. It was a great group of people from all over the world. All of us got increasingly frustrated with the lack of financial transparency, the management and also with the direction TIES was taking. We tried and tried to resolve the problems internally. After the successful ESTC 2014 in Bonito, the Advisory Board came to the conclusion that it could not support future ESTCs without a deeper understanding of the financial risks.

In response, TIES quietly removed the Advisory Board from their website without communicating this to us first, and we therefore publicly resigned as a group. We then discussed if it was worth setting up a new organisation and contribute to carrying the flame for ecotourism and be a beacon for sustainable tourism.

What makes GEN different is the many years of practical experience in all aspects of ecotourism.

We have seen products, destinations and tourism organizations start up, grow, try, fail and innovate. There is a lot of reinventing the wheel and lost opportunities in ecotourism and we think that we can help focus on the issues, that make a difference. GEN aims to be a global network that is very hands on.

Anything else you’d like to mention?

One of the advantages of getting older is that you can see how things turn out. I tend to follow projects and initiatives I have been part of.

When I researched the Kemp’s Ridley Turtle in Mexico it was on the brink of extinction with less than a 1000 nests per year, less than 1% of the 1947 level. But thanks to long term cooperation between Mexico and the US, numbers rebounded to over 20,000 in 2012. At the moment, researchers are worried again as numbers are falling, which might be an effect of the Deep Water Horizon disaster, but also a decline in their favorite food, the blue crab. Today turtles are an important tourism attraction in many places. Tamar in Brazil is a great example of that.

The Golden Lion Tamarin is also an interesting example. The population that was on the brink of extinction in the wild in the 60s, is now already over the target set for 2025, and a key problem now is assuring enough protected rainforest and ecological corridors. The protected areas, which are usually private, offer new opportunities for tourism.

It is also important to remember that we are all “dwarfs standing on the shoulders of giants”.

The Golden Lion Tamarin is now a tourism attraction, because a Brazilian primatologist, Adelmar Coimbra Filho, managed to rally both the Brazilian and the international conservation community to save it. The Uakari Floating Lodge at Mamirauá, for which I did the original business plan, was built to support economic alternatives in a sustainable development reserve. The reserve was created through the efforts of Marcio Ayres, who did his thesis on the rare and endemic Uakari Monkey. And he was inspired by 19th century explorer Henry Bates, who wrote The Naturalist on the River Amazons.

Thank you, Ariane.

Learn more about the Global Ecotourism Network, EcoBrasil or connect with Ariane Janer on LinkedIn.

Enjoyed our interview with Ariane Janer on Eco Brasil and the Global Ecotourism Network? Share and spread the word!